Bannerman of Brooklyn.

As part of a larger study of the trade in surplus military rifles at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, and in particular trying to answer the question of how a Swiss Vetterli rifle in my collection happened to have the initials and address of someone in a small town in Ohio crudely scratched onto the receiver, I’ve encountered a number of extraordinary characters. One of the most interesting is the successful and flamboyant Scottish-American surplus dealer, Francis Bannerman of New York.

Francis Bannerman VI was born in Dundee in 1851. In 1854 his family emigrated to America and by the late 1850s were living in Brooklyn where his father (Francis Bannerman V) supported the family by selling scrap and surplus goods he bought from the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In later, more comfortable, years Bannerman related the story of his success by reprinting a long piece from “Appleton’s cyclopedia of American Biography” on the very first page of his mail order catalogue.

How much of it was true is hard to say. The account certainly contains many conventional “rags to riches” elements, but it seems to be the case that young Francis had a tough time of it when his father went off to war to fight for the Union. The young Bannerman was forced to leave school and earn a living. He got a job as an “errand boy” for a law practise situated just off Wall Street. Rather more alarmingly, he also acquired a “captured southern dugout canoe” which he used to paddle around the crowded and dangerous waters of Navy Yard bay and sell newspapers to the crews of the warships anchored there. By 1863 he had expanded his business portfolio with the help of an old anchor with which he trawled the waters of the bay, recovering lost or discarded pieces of rope and chains which he could then resell. By the time his father returned from the war, disabled by his service, this remarkable young man had kept food on the family table and demonstrated an enormous capacity for hard work, a willingness to take risks and an entrepreneurial spirit that would stand him in good stead in the future.

Bannerman said that he started buying military surplus as early as 1865 when he would attend government auctions in order to buy old swords and weapons purely for their value as scrap metal. The rewards could be substantial. An old musket would “net about 7 pounds of iron”. An interrelated ecosystem of dealers large and small took advantage of the huge amounts of military surplus that were generated by the American Civil War and Bannerman had dealings with many of them. For example, in 1885 he formed a business relationship with JW Frazier, a military surplus dealer and agent of the Spencer repeating firearms company, a company he would buy in 1890. The records also show he had regular contacts with the company “Schuyler, Hartley & Graham”, also of New York, who had become the largest wholesale supplier of firearms in America in the mid 1800s, and, after their success in supplying the desperate French during the Franco-Prussian war ‘the most prominent firearms dealer of the 19th century.”

His business dealings could be fractious. Bannerman knew the value of a Dollar, almost to the point of “canny Scot” self-parody. In 1906 he wrote a series of increasingly irate letters to H K White, who acted as the head of SHG’s warehousing and order fulfilment department. Bannerman had purchased an old bronze cannon from him with the intention of breaking it down and selling the bronze (at 10c/pound) as scrap. However the cannon turned out to be rather less weighty than the 1854 pounds estimated and as such Bannerman demanded a refund on the price he’d paid. He asked Mr White for a check for $7.20 (about $200 in 2021). We don’t know how it turned out, but Bannerman ended one letter to White by leaving the matter “entirely to your own sense of honour”.

Compared to these huge dealers Bannerman was a minnow, yet he is still remembered. I suggest that’s because he left two great monuments behind him, one in crumbling stone, and the other in yellowing paper.

Bannerman became an American citizen in 1872, the same year in which his father died. He continued to buy and sell pieces of surplus military equipment, “rope, canvas and metals” and general goods including potatoes and other “country produce”. His business grew, but progress was slow. In 1884 Bannerman attempted to increase the reach of his business by issuing a mail order catalogue in the form of a hand written list of military surplus goods. By 1888 the catalogue was professionally printed, though only 12 pages long. Eventually this modest list would grow to a contain hundreds of fully illustrated pages and become the first of his two great monuments: the famous “Bannerman catalogue”.

I’d argue that it’s the catalogue that really differentiated Bannerman from his competitors. They may have been successful businessmen but Bannerman wanted to be more than that. He had a mission. He believed, or said he believed, that he had to preserve the historic weapons he saw being destroyed as so much scrap metal. He would save the old swords and weapons that would otherwise be “consigned to the fire”. Not only would he save them, he would teach the world about them. This he intended to do through the medium of his catalogue, which would contain not only a list of goods for sale, but also information on the history of weapons. He would also create a “museum” of sorts in his retail store at 501 Broadway which he opened in 1905. Bannerman made his lofty intentions clear in a preface to his catalogue where he said:

“We believe the millennium will come, and have for years been preparing by collecting rare weapons now known as ‘Bannerman’s Military Museum’ but which we hope someday will be known as the “Museum of Lost Arts” when law and order will be preserved without the aid of weapons”.

It’s impossible to know how sincere he was. To our modern eyes his biblical allusions reek of hypocrisy. Perhaps his faith allowed him to rationalise and excuse the fact that he was an arms dealer and perhaps his desire to educate was that of the autodidact, forever regretting that his father’s illness had prevented him taking up the offer of a scholarship to Cornell University. Whatever his motivation it’s true that his catalogue became the extraordinary product of one man’s desire to teach the world about weapons while simultaneously selling them in large numbers. Carnegie may have had his libraries, but Bannerman would have his catalogue.

The second monument was his bizarre “Castle on the Hudson”. It may have seemed more enduring, but the Bannerman family would find out that mixing amateur architecture and gunpowder could have terrible consequences.

This extraordinary piece of half baked Scottish Baronial architecture began in 1900 as a solution to a problem which was, ironically, caused by his greatest success.

This success came as a result of the brief but bloody Spanish-American war of 1898. The American forces captured all manner of weapons and military equipment from the defeated Spanish and, in a stroke of genius, Bannerman pretty much bought the whole lot from both the US and Spanish governments. The array of weapons and stores was a bewildering but wonderful opportunity, ranging from Remington rolling block rifles and large quantities of ammunition, to Hotchkiss revolving cannons, to torpedoes, to eighteenth century bronze cannon. By not quibbling about separating the good from the bad and just buying everything Bannerman had paid a bargain price. By judiciously selling the best quality weapons and breaking up the dross, he could make a fortune. The only problem was that he had nowhere to keep such huge quantities of gear, and unsurprisingly, the residents of Brooklyn were not happy with him storing what he claimed to be 30,000,000 rounds of black powder ammunition in their neighbourhood.

Bannerman’s answer was to buy the small Pollepel island on the Hudson. It was a small rocky outcrop fifty miles away from the city but within easy reach by boat. By the end of 1901, the “Number 1 Arsenal” had been completed and in an act of assiduous self-promotion, Bannerman made sure anyone travelling the Hudson by boat or train knew who owned the island by whitewashing the huge structure and painting a billboard across it proudly stating that here stood “Bannerman’s Arsenal”. Development continued on the island and by 1918 it was crowded with another two “Arsenals”, a powder house, harbour and shipping facilities and the extraordinary confection that was the castle or “lodge”. Bannerman designed most of the buildings himself, quite often by handing his builders crude sketches some of which were quite literally on the backs of envelopes and expecting them to get on with turning his dream into reality. If they failed to match his vision the buildings would be torn down and started again from scratch. Their style was, to be polite, “eclectic” and their construction quality reflected the speed with which they were built and the fact that the back of an envelope isn’t a detailed blueprint for a building. Nevertheless, by 1918 the warehouse and castle were a giant advertisement for Bannerman and helped make him famous.

By the early years of the twentieth century Bannerman was rich and successful but he could not stand still. The American hunger for surplus military gear seemed never ending but he still felt the need to travel the world searching for new markets and sources of supply. He made a number of buying trips to Europe, including at least one to Switzerland, where I believe he bought the Vetterli rifle that now lives in my collection. Although he was economical with detail and may have exaggerated his success, he probably also sold large quantities of weapons to governments as well. In his catalogue (in a section honestly titled “Blowing our own horn”) he claimed to have sold Mauser rifles purchased after the Spanish-American war to “European and Asiatic Governments”. Exaggerated or not, he certainly sought opportunities in Asia. Perhaps through his contacts with the Hamburg arms dealers he knew about the instability of the area and the huge quantities of weapons both old and new that washed around it. This was an opportunity to both buy and sell. His extended trip to China and Japan in 1904-1905 must have been somewhat arduous for a man in his fifties, but it was at least undertaken in some luxury; the archives show he stayed at the Astor House Hotel on the bund in Shanghai which was, at the time regarded as the “best hotel in the whole of the East, including Japan”.

Bannerman had made his fortune from war but with an irony that seems common in the stories of arms dealers it would be war that would see the start of the slow decline of his business

Bannerman was a proud American but also a proud Scot who wished to do his patriotic duty. As reprinted in his catalogue his biography stated that during the First World War he donated “thousands” of rifles to the British “in their great fight”. The reality was somewhat less impressive. What Bannerman sent the British was no more than 1000 rifles that rather summed up his business in one messy object. “Bannerman’s .303 rifles” were a somewhat disturbing mix and match of rejected and surplus parts. The receivers were from 1903 Springfield rifles that had failed US army inspection because their heat treatment had been ineffective which left them brittle and liable to fail. These were reheat-treated by a company called R.F. Sedgley and matched with a barrel (rebored to .303) and sights from an American Krag rifle. The rifle stock came from another Springfield, the hand guard and magazine follower came from a Mauser and the rifle was completed with some newly built parts. The weapon was proudly marked with Bannerman’s name and his trademark of a hand holding a union flag.

One can only imagine the reaction of the recipients of these gifts. The weapon never really worked because it had not been designed for a rimmed cartridge so feeding was consistently problematic. They could hardly have inspired confidence. The weapons were used for drill purposes only and quietly forgotten about. Like his buildings, the Bannerman rifles were jerry-built and had questionable structural integrity.

Bannerman may have been cheap, but he could never have imagined that anyone could question his patriotism. Sadly, that’s exactly what happened. In 1918 Bannerman’s island came to the attention of the US Naval Intelligence Bureau who had become nervous about the huge quantities of weapons and explosives stored close to the West Point military academy and the vital transport route that was the Hudson river. Their suspicions appeared to be justified when they discovered that one of Bannerman’s supervisors on the island was an Austrian called Kovacs. They were even more horrified when a search of the island found that machine guns had been sited in the complex, apparently ready to fire at river traffic. Bannerman had to fight to prove that Kovacs was innocent, that the machine guns were second hand and used only for firing salutes with blanks and to stop the government occupying the island and seizing the goods held within it. In the end he was completely exonerated, but it’s speculated that the strain of the fight combined with gall bladder surgery led to his death in 1918.

There was no more building on the island after his death. In 1920 the powder magazine exploded, destroying some of the buildings and revealing just how badly built many of them were. The island continued to decline and was sold by the Bannerman family in 1967. A huge fire in 1969 saw its final dereliction.

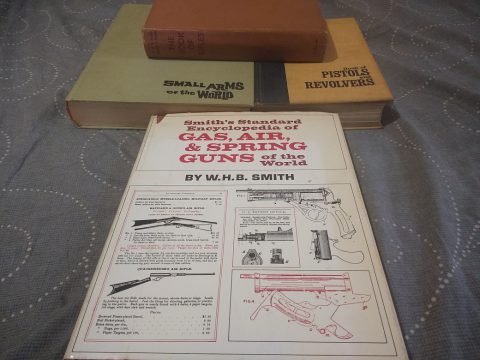

The catalogue also suffered a decline which mirrored the business as a whole. As the years went on it’s clear that no-one was buying stock with the same manic intensity as Francis had done. His sons who took over the business after his death did not buy in bulk from the US government to anything like the same degree as Francis had done, concentrating on buying from state Government sales and from individual collectors of antique weapons. Sales slumped in the 1930s because of the depression and the plethora of surplus from the Great War that flooded the market and drove down prices. The 1945 catalogue in its deluxe edition was a handsome, leather bound affair, but the contents were pretty much the same as they had been for many years. The shop at 501 Broadway was sold in 1957 and turned into a parking lot. Before the site was cleared a surplus dealer called Robert Pins visited the site and saw first hand what had become of Bannerman flagship. It had “fallen into seedier days” and was now a “totally disorganised jumble” of musty uniforms, bent rifle barrels and rotting leather harnesses. By 1959 both of Bannerman’s sons were dead and the business was run by his grandson, Charles S Bannerman. By 1965 and the 100th anniversary edition of the catalogue much of the content was made up of reprints from earlier catalogues and reminiscences by the Bannerman family. It was to be Bannerman’s epitaph. Despite the confident assertion that the business would continue from a new facility in Blue Point, New York, the business was fading away. Charles eventually sold what remained of Bannerman’s stock to another dealer, who must have wondered what he’d got himself into when he saw the shambles that remained.

In the end we can see Bannerman as a fine example of the nineteenth century American “self made man”. His hard work and devotion to both God and business made him rich. He may have died disappointed by how his adopted country treated him, but he would certainly be pleased that his two “monuments” mean that his name, unlike so many other arms dealers of the era, has not been forgotten

The “Castle on the Hudson has gained a place in American popular culture, appearing in TV programmes and used as a film set in a “Transformers” movie. The island and its buildings are currently administered by a trust who offer guided tours of the increasingly dangerous ruins and use the site as the backdrop to events and dramatic performances.

https://bannermancastle.org/

Bannerman catalogues are available in facsimile form and some have been digitised. The Royal Armouries in Leeds holds a collection of them in their archive, which may be visited by appointment.

My thanks to the team at the Armouries for their help in producing this piece.

Interested in Military Rifles and the Arms Trade of the late Nineteenth Century. Loves the smell of archives in the morning.