Back in the 1950s, when Americans loved revolvers and department stores sold guns, Sears sold hunting and other recreational firearms under its J. C. Higgins sporting goods house brand. One of the companies they had a regular relationship with was Hi-Standard, who manufactured white label shotguns and rifles for them. Seeing a market niche for a house brand .22 sport revolver as an alternative to the excellent but expensive options from Colt, Ruger, and S&W, Sears commissioned a light, handy, aluminum-framed revolver to fill that niche–to have an option to offer the customer who clearly wants a .22 Smith but is hemming and hawing on price.

Hi-Standard delivered the Sentinel

(sold by Sears as the J. C. Higgins Model 88) in 1955. The Sentinel is an aluminum framed double-action nine shot sport revolver with a swing-out cylinder. It’s not a small frame, so the full sized cylinder holds nine rounds of .22lr. Like many budget revolvers of its time there was no cylinder release button; you pull the ejector rod forward to unlock it (originally there was no return spring on the ejector rod either, so you had to retract it manually; a return spring would be added after a few years of production.) They were sold in several configurations as a recreational plinker, small game handgun, budget target shooter, camping kit gun, and even a self defense firearm. Proving that there’s no new marketing gimmick under the sun, the Sentinel was also advertised as a friendly, light-recoiling defensive option for the gun-shy lady in your life, sold in a variety of kitschy color finishes with fancy presentation boxes.

Though Sears would drop their handgun line in 1963 due to growing political pressure, Hi Standard would continue selling the Sentinel family of revolvers into the 1980s, with substantial upgrades in the 1970s. That decade saw Sentinels with steel frames, walnut grips, optional adjustable target sights, and a .22 WMR version (and early in the new run, you could get a set that came with interchangeable .22lr and .22 magnum cylinders). The Sentinel name was also used in the 70s for rebadged .357 magnum Dan Wesson revolvers, but that’s a-whole-nother animal.

By 1958, the TV western craze meant Ruger was basically printing money with its Single Action Army-inspired sixguns, Colt itself had gotten back in the game producing the authentic second-generation SAA, and even a company in as tight a place as Great Western Arms could limp along as long as it had cowboy guns to ship. Hi-Standard and Sears wanted a piece of that action as well, and decided to release a budget competitor. But tooling up a whole new gun takes work, time, and money, and they already had a revolver in production– …and other gun companies had proven that there was a market for .22 versions of the SAA in particular, like the Ruger Single-Six and the brand-new Colt Frontier Scout. Great Western seems to have sold more of their Peacemaker clones in .22lr than in any other cartridge, and actually one of the things that contributed to the end of that company was price competition with cheap .22 SAAs that Hy Hunter imported from Germany. Rimfire cowboy guns were big business. Hi-Standard cheated a bit and “leveraged existing resources” to bring a product to market.

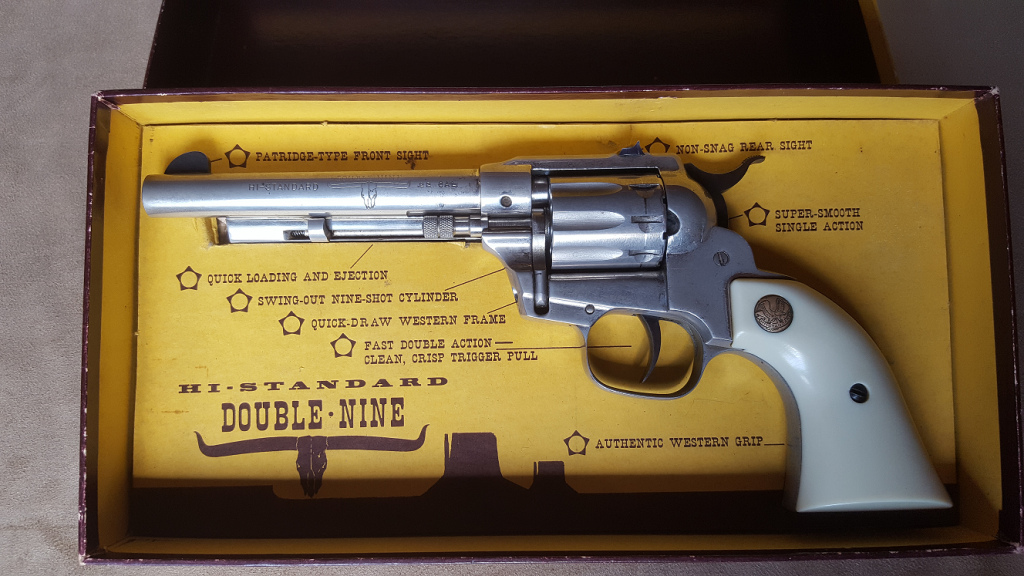

The result is the fuddliest gun I own: The Hi-Standard Double-Nine, also sold for five years as the J. C. Higgins Model 90 “Ranger”. It’s a double-action Sentinel, tarted up to look like a cowboy gun with an externally reshaped frame, hammer, and trigger, and a fake ejector rod housing under the barrel. The fake ejector rod tab can be pulled forward to work an extension that pulls the actual ejector rod, unlocking the cylinder. It’s far from the most authentic SAA, but there was a market for “modernized” cowboy guns like the Blackhawk and Great Western Deputy, and the Double-Nine was well received. Even Elmer Keith gave it a positive review.

This one is a model W-100, making it part of the very first run of Double-Nines, before they added the ejector return spring (at some point somebody tried to close it without retracting the ejector star, so it has the Hi-Standard equivalent of a 1911 idiot scratch.) The W-100 model was made in 1958 and -59, and the serial number suggests this particular example was most likely shipped in the first two months of 1959. It came with the magnificently kitschy original box. The end label has the serial number handwritten in grease pencil, and the box interior advertises all the double-action Sentinel features that are totally performance enhancing design decisions and not just the result of jury-rigging a DA revolver into a cowboy gun. The manual is missing, but a PDF Version is available from the High Standard Collectors’ Association. This crumpled price tag was stuck to the bottom of the box; the price is way too low for the revolver even in the 1950s, but it may be from the same store. Unfortunately there’s no way to be sure. It has a nickel finish, which was an extra five bucks back in 1959.

Hi-Standard certified these safe to dry fire in the manual, and I do believe that’s true. The chambers are all counterbored and the fixed firing pin on the rebounding hammer only protrudes very slightly when down all the way, so the pin itself looks to never make contact in an unloaded gun–but I’m still using yellow drywall anchors just to be sure.

On this early model, the hand pushes against round holes in the back of the cylinder rather than traditional ratchet teeth. Hi-Standard marketed this as a design improvement that improved lockup and minimized timing issues due to wear. I have no idea whether any of that is true, and don’t have a later toothed version to compare to, but at least on this example the cylinder locks up absolutely at full lock when the trigger is pressed after cocking, with no wiggle whatsoever. The double action is very, very heavy and difficult to stage. In general I’m pretty comfy with DA, but this one gives me a great deal of trouble holding it on target through the cycle. Apparently it’s fine if you’re Elmer Keith. But the single action is very, very nice, especially for a revolver designed to undercut the existing market on price. The overall impression the Double-Nine gives is of a budget gun in which corners may have been cut in looks, but the mechanism is still perfect where it matters most for the intended function. In my limited experience, that’s pretty much exactly what I expect from Hi-Standard’s economy guns.

The action can’t be fanned like most single-actions: the cylinder will revolve and the pistol will fire for the first round, but every subsequent cycle of the hammer will fall on the same spent cartridge. This is no big deal today, but I expect it disappointed a lot of aspiring trick shooters back in the 50s. The hammer is rebounding and has a hammer-block drop safety. Hi-Standard revolvers seem to have a reputation for accuracy, but I haven’t gotten a chance to shoot this one yet; it’s the first firearm I’ve ever bought primarily for collecting rather than shooting.

This crazy aluminum frankenpistol is a paragon of fuddery. Like the Blackhawk, it’s a retro-1950s-retro-1870s slice of pop gun culture, marrying the classic American cowboy blaster to the market, mythology, and technology of the postwar Atomic Age. I’ll bet Hi-Standard went out of its way to make the thing dry-fire safe because they knew these little six-shooters would be snapped at bandits on the TV more often than they’d be fired at cans and bunnies.

I bought this one out of a love of retrofuddery and things that are old. There’s a satisfaction in objects that evoke their own time and place, and this department-store sixgun from 1959 really evokes the hell out of 1959. This particular firearm was made within a few months of the statehood of Alaska (and the announcement of the statehood of Hawaii); the establishment of the current government of France; the foundation of the Jim Henson Company; the launches of Luna 1 and Pioneer 4; the declaration of Vatican II; the premiere of Sleeping Beauty; the Dyatlov Pass incident; the plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper; the communist conquest of Cuba; and the introduction of the Barbie doll. It was a vivid time, and a person can tie up a whole lot of that vividness in an object that seems to have spent all the years since then kicking around the same region in eastern Pennsylvania.

The Double-nine is a less common variant in the Sentinel family, but there are still a ton of them out there and just about nobody collects them; so prices tend to be extremely reasonable for what you get. I bought this one, a less-common variant, in good condition, from the first year of production, in the original box, in the rarer nickel finish, at a local store known for having high-ish prices– …and I paid $360. Adjusted for inflation, that’s less than it sold for brand new in 1959 (about $425 in 2018 money). Examples with surface wear and cosmetic issues are commonly available on Gunbroker for under $300, and if you’re patient and not particular on details, they can be found under $200.

tablinum,

First time here and am trying to find out if anyone knows if the early W-100 can be upgraded to the extractor return spring?

Thanks