Andrew Burgess is, perhaps, one of the greatest “forgotten” American arms designers. Born in Dresden, New York in 1837, he and his family would later relocate to Owego. This is where he would establish his workshop and begin a long list of patents that eventually grow to nearly 600 in number. First, however, he had to take some pictures. Burgess was also a photographer and employed by the famous Mathew Brady. There is evidence to suggest Burgess may have actually taken the photograph of Abraham and Tad Lincoln, and the profile featured on the five dollar bill. Burgess would eventually buy out Brady’s business, but later sold it back. From there he profited more from invention, having patented and successfully sold a fire alarm. In 1871 he would patent ideas for converting Peabody and Werndl rifles into repeating guns. Ultimately his successes allowed him to keep several men in his shop sharing in the effort to develop new designs.

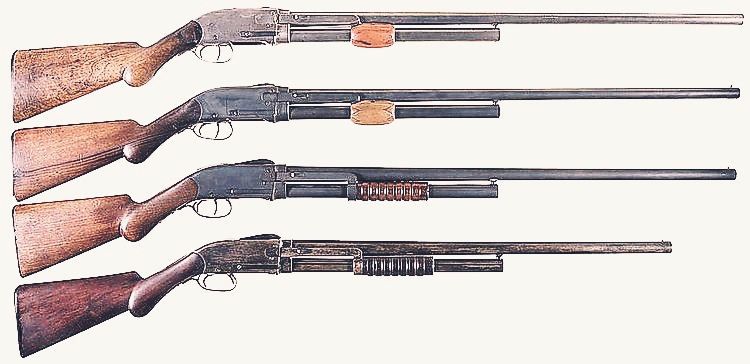

Burgess’ first well-known firearms would emerge from an 1872 patent, developed into several models that quickly caught the eye of Eli Whitney, Two of its three major variations would be made under his name, and then further modified under the name Kennedy. These lever action repeaters represent the large bulk of Burgess history being discussed in firearms literature. However, today we are discussing his LAST design: a repeating, slide action shotgun.

In 1893 Andrew Burgess would found his own company in order to produce a new firearm of his own design. The patent covered a unique repeating action that could be made into a rifle or shotgun; though the latter came first. Hitting the market in 1894, the state-of-the-art Burgess Gun received nothing but good press and high marks from early observers. Pricing was as low as $40 for a “Grade D” gun and up to $200 for a finely engraved, premiere firearm.

Mechanically it is a 12 gauge, slide action operated, locking breech shotgun. Nothing about that initial statement seems fantastic until you release the slide assembly carries the trigger and wrist, semi-pistol grip and all! Locking is achieved by a tipping block attached to the breech-block, which drops at the rear when the action is closed. The trigger may not engage the sear until lock is achieved, preventing out of battery fire. Initially the Burgess Gun shipped without an inertial safety, which made it vulnerable to hang-fires during rapid fire. These were more common in the early days of smokeless shotgun loads. Guns with the later inertial safety require the shooter to press forward on a button at the front of the trigger guard in order to open in action unless it has been shot. The action, when closed, is completely sealed by the breech-block and an underside action cover. Loading the gun requires opening the action, assuming the gun is assembled

Take-down, as in easily disassembling the gun into roughly half for travel, is easily the simplest of any period shotgun. Since there is no action bar forward of the receiver, you only need to slightly withdraw the breech-block (clearing the extractor from the barrel) and depress one button to slide the barrel and magazine assembly out of the receiver’s locking lugs. That’s it, just one tiny button! It’s worth noting that the magazine assembly-side of the gun carries the cartridge stop, so you can load the magazine disassembled and simply slide it back in place!

Period advertising sometimes referred to the Burgess Gun as “semi-automatic.” This is not under our current definition, as any autoloader would be called “automatic” at the time. Instead the Burgess is manually operated but took unique advantage of shooting physics. Any rearward draw on the grip would immediately open the action. So at the very moment of a shot the first wave of recoil sends the gun rearward, as the shooter’s hand remains still. This keeps the gun locked for just that first instant. Once the recoil is transferred to the shooter, their hand now travels rearward. If the shooter were to favor a rearward pull as they fired the gun, they would find the residual recoil momentum aiding their draw on the mechanism: snapping it open rapidly and sharply with almost no effort. Then simply drive the mechanism forward to fire again. Unfortunately this took some getting used to and we’ve found most modern shooters fight the mechanism at first.

An interesting point further in favor of the Burgess Gun is that it is completely symmetrical in design, making it inherently ambidextrous. This was further evidenced by their hiring of professional exhibition shooter “Left Hand” Charlie Damon, along with several right handed people as well, to market the gun at various public events. The fine handling and rapid shooting was put to work to prove their motto “Six hits in less than three seconds.” Given the unique recoil aid and the fact the gun is capable of “slam fire” and we find these numbers easily achievable.

Now most turn-of-the-century shotguns came in roughly three configurations: standard, field (or brush), and riot. While a myriad of minor changes abound, generally the difference was just a matter of barrel length. The Burgess gun did one better. Because of the unique slide action, set behind the receiver, the gun wasn’t just easier to take down in halves; it could actually be hinged! With this in mind, Burgess took a patch from the Smith carbine and fixed an overhead spring. Now the gun could not only be folded, but snapped back into assembly with the flick of the wrist. This quick deployment meant the gun wasn’t just stowable, but that it could be carried holstered on the hip and drawn as rapidly as a revolver.

In order to enable folding, the gun features a massive hinge at the bottom front of the receiver. The interrupted lugs of the take down assembly are now only at the top of the receiver. A set of guide pins, really just projects from two new screws in the side of the action, ride in curved channels on either side of the barrel assembly. When shut, these pins settle into their own recesses and add rigidity and some additional lower locking strength to the action. When unfolded, the massive overhead spring is responsible for holding the barrel assembly upward, forcing the locking lugs to engage for firing. A T-shaped lever is set inside the spring and is flipped up 90 degrees in order to release for take down.

Burgess marketed the gun as a 6-shooter, but we found the magazine only held five rounds… until we cleared our misconceptions. The Burgess magazine will hold six rounds of 2½ inch 12ga cartridges which were still commonly found at the time. So marketing assumed an empty chamber. However, we’ve found that a bit of grease or wax will keep a pre-chambered cartridge in place long enough for demonstration shooting. Although I should warn that the firing pin does NOT rebound and if you were to try and flip-assemble a loaded chamber with the hammer down… well it has a high likelihood of discharging inopportunely.

Period advertising named Police, Express Messengers, Marshals, Prisons, Bank guards, and others to wear the Burgess on their hip. It even included a triptych depicting concealment under a mid-length top coat, followed by the draw. A Burgess folding gun would cost you $30 in 1895, $10 more for a Damascus barrel. The holster was only $1.50 extra and well worth the price! We’re having one reproduced from an original example and the thoughtfulness that went into the construction is the reason these have lasted over 100 years. Every stitch was considered carefully in design.

Period advertising named Police, Express Messengers, Marshals, Prisons, Bank guards, and others to wear the Burgess on their hip. It even included a triptych depicting concealment under a mid-length top coat, followed by the draw. A Burgess folding gun would cost you $30 in 1895, $10 more for a Damascus barrel. The holster was only $1.50 extra and well worth the price! We’re having one reproduced from an original example and the thoughtfulness that went into the construction is the reason these have lasted over 100 years. Every stitch was considered carefully in design.

A story has long been told of Theodore Roosevelt’s first encounter with the Burgess folding gun. I’ll repeat it here with the warning that I have not been able to track it back to its origin. In 1895, Roosevelt had taken, briefly, the position of President of the New York City Police Board. One day he was visited by “Left Hand Charlie” on behalf of the Burgess Gun Company. Intending to sell the police department his gun, Charlie had taken the bold decision to load one full of blanks and hide it under his coat for the meeting. Entering Roosevelt’s office he drew the shotgun and fired off six rounds skyward, or ceilingward in this case. I don’t suppose a little more tinnitus was much of a concern for Roosevelt, as the New York Penal System would purchase 100 of the guns.

Burgess would begin marking a rifle using the same action as his long shotgun in 1896. Because of the unique take-down method, having spare barrels of different length was an easy luxury. The following year brought out folding models in .30-40 Burgess, .30-30, and .44-40. Unfortunately these are rare in the extreme today as the company did not last much longer. It struggled against Winchester’s aggressive advertising and pricing strategies. Andrew Burgess was now a much older man and in 1899 would agree to sell out to Winchester, who happily folded another competitor company away. They did not opt to continue production of any of these shotguns or rifles, favoring their own models instead.

If you’d like to see a Burgess in person and learn more about this period in firearms history, we would recommend visiting the Cody Firearms Museum as they are the custodians of the Winchester records and much of their arms collection.

C&Rsenal releases their flagship series “Primer” every other week. It focuses on one firearm of the Great War at a time, in depth with animations, live fire demonstrations, and historical context! Our mission is to document and describe historical military small arms from across the world. We hope to share our love for all the attention that went into the design, development, manufacture, and issuance of these pieces.