Introduction

In the scramble to acquire small arms in the midst of a chaotic civil war and with the backdrop of a largely noninterventionist international political sphere, the Spanish Republic’s difficulty of securing modern or at least relatively-modern weapons was such that only a few, disparate international sources were able to be reliably brokered — mainly originating from the Soviet Union, Poland, and Mexico, though other nations also committed material support to lesser extents.

This article focuses on the nonstandard, foreign-supplied rifles in use by the Republican Spanish in the Spanish Civil War of 1936 to 1939, drawing on a number of primary and secondary texts and period photographs, with the aim of providing a comprehensive analysis of their direct international sources, front-line use, and postwar collection and surplus. As the effects of the Spanish Civil War are still internationally felt decades later, this article is presented from a politically neutral perspective, with respect to the complexity, nuance, and tragedy of the conflict and its aftermath.

Standard Rifles of the Spanish Army: Domestic Mausers

The most prevalent rifles in use during the Spanish Civil War among both armies were that of the 1893 pattern Mauser and its 1916 short rifle variant; both standard arms of the prewar army chambered in 7x57mm. Initial production of the 1893 pattern rifle was undertaken at Mauser Oberndorf and Ludwig Loewe & Co., as well as domestically at Fabrica de Armas Oviedo — these early production rifles bore the Spanish national crest and their stripper-clip fed, five-round staggered internal box magazine distinguished them from American Krag-Jorgensen rifles during the Spanish-American War of 1898.[1]Ludwig Olson, Mauser Bolt Rifles (Montezuma, IA: Brownell & Son, 2002), 65-7. In the intervening period, the 7mm 1893 pattern Mauser rifle remained the standard rifle of the Spanish army, continuing service through the Rif War and up through the Civil War.

The development of a short rifle variant in 1916 produced a rifle based on the 1893 action, but incorporating a turned-down bolt handle and a pair of front sight protector wings. Early variants were equipped with lange vizier-style rear sight, though most are encountered with standard, flat tangent sights.[2]Olson, 73. Production of the 1916 short rifle was undertaken at Fabrica de Armas Oviedo up to and through the Civil War; as that arsenal remained under Nationalist control, a number of 1916 short rifles bearing a dated “INDUSTRIAS DE GUERRA DE CATALUNYA” or “SUBSECRETARIA DE ARMAMENTOS” rollmark on the receiver ring are evident of limited Republican production during the conflict.[3]Robert Ball, Mauser Military Rifles of the World (Iola, WI: F + W Media, 2011), 353.

As the initial coup ushering in the conflict originated from within the national army, the logistical chaos of the Civil War left Republican forces desperate for small arms; though domestic 1893 and 1916-pattern Mauser rifles were common, their numbers were not sufficient to arm either the remaining troops nor the ones recruited by political or regional militias. Consequently, the reorganization and consolidation of Republican militia forces and scattered loyal military units into the Ejército de la República Española in 1937 helped to mitigate some organizational issues, but did little in the way of easing logistical strains or standardizing small arms.[4]Burnett Bolloten, The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 330. The Republic would be largely dependent on foreign weapons and supplies.

Rifles from Soviet Sources: Spanish gold for the Czar’s broken toys

In the interest of securing arms and other military materials, the Republic’s appeal to the Soviet Union was a logical one — aligned political ideologies and the Soviet Union’s interest in unified international communist movements seemed ripe for the potential of direct material support for the beleaguered Republic. However, arms and other materials would not be supplied purely altruistically: in October 1936, transfer of the bulk Spain’s gold reserves, valued at $500 million, to Moscow would cement Republican primary reliance on Soviet aid,[5]Bolloten, 145–58. with additional purchases made on credit throughout the war.

Early Soviet efforts in 1936 to collect and transport military material to the Republican Spanish came under the direction of the NKVD, resulting in a series of policies under the title “Operation X,”[6]Stanley Payne, The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), 141–44. taking the form of six series of discrete voyages of Soviet freighters to Republican-held ports. Under the auspices of military assistance detailed in Operation X, logistical efforts to eliminate older, nonstandard weapons in Red Army inventory left over from Imperial efforts to source small arms abroad during the First World War,[7]John Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight,” Guns Magazine, April 2005 and those fielded in the subsequent fighting following the revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War.[8] Payne, 156–57. Generally, these weapons were obsolete and in poor condition; however, their arrival throughout the late fall of 1936 permitted much-needed weapons for desperate Republican troops.

Gerald Howson’s analysis of Soviet shipping manifests associated with Operation X details the variety and obsolescence of ex-Imperial Russian weapons; small arms delivered by Soviet voyages from September of 1936 to January 1937 mostly consisting of obsolete foreign types originally purchased abroad during the First World War.[9]Gerald Howson, Arms for Spain (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), 136-39, 278-85.

Among these foreign types, taken into Soviet inventory following their use in the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922, were the following: 3,658 Austrian 8x50R Mannlicher rifles of all types; 10,000 11mm French Gras rifles along with 1,821 1878 Gras-Kropatschek rifles in the same caliber; 1,242 French 8mm Lebel and Berthier rifles; 13,357 Italian 10.4x47R 1870/87 Vetterli-Vitalis; 6,000 7.92 German Mauser rifles of all types; 3,202 .303 Lee-Enfield rifles of the older Magazine Lee-Enfield and more-modern Short Magazine Lee-Enfield varieties; 9,000 American-contracted Winchester 1895 lever actions chambered in 7.62x54R, and unknown quantities of .303 Canadian Ross Mk.III rifles and 6.5×50 Japanese rifles of all types.[10]Howson, 138.

Of the rifles supplied to Republican Spain, those of French origin made up the remainder of shipments sold to the Czar’s government during 1915 through 1917; the 11mm single-shot black powder 1874 Gras rifles and the tube-fed 1878 Gras-Kropatshek were long obsolete, having been consigned to French reserve stockpiles in the prewar era. Sheehan cites the initial sale of 450,000 Gras rifles and 150,000 Gras-Kropatsheks in 1915;[11]Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight.” the comparatively low numbers retained in Soviet reserve and subsequently sold to the Republic in 1936 may be a result of wartime attrition during the First World War and Russian Civil War or perhaps because of their limited utility in comparison to more modern designs. These rifles were among the first to reach Republican ports in the autumn of 1936; allegedly shipping with only 385 cartridges each,[12]Howson, 139. the utility of these 11mm black powder rifles would wear thin quickly, and photos of their use seem to only date from late 1936 and early 1937.

Of greater use — but certainly in little better shape — would be the French 1886 Lebel and Mle. 07/15 Berthier rifles. The former, incorporating a Kropatshek-style tube magazine and chambering the revolutionary 8mm Balle D smokeless round would turn the military small-arms world on its head in 1887, inspiring other nations to quickly adopt competitive designs. However, its modernity had been surpassed by the declaration of war in 1914, and the development of the three-shot, en-bloc fed Mle. 07/15 Berthier infantry rifle from a series of prewar cavalry and colonial carbines helped to supplement the 1886 Lebel in French wartime frontline use. Initial Russian shipments of both rifle types totalled 86,000;[13]Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight.” service in Republican hands would be extensive, though greater numbers of Berthier rifles and carbines would additionally be sourced from Poland.

Sourced by the Imperial Russians from the Kingdom of Italy in 1916, the large-bore 10.4x47R Vetterli-Vitali rifles had the advantage over the single-shot Gras in that they fed from a four-round, charger-loaded box magazine, but they were still scarcely modern at the turn of the century, having been largely replaced by the 1891 Carcano rifle in Italian service. Howson erroneously speculates the Russian source of these rifles as having been captured from Turkey in the 1877 Russo-Turkish War,[14]Howson, 139. but in reality, Sheehan cites 400,000 taken into Imperial Russian service during the First World War.[15]Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight.” Surviving Vetterli-Vitalis would be sold to the Republican Spanish in late 1936 with a scant total of 185 cartridges per rifle, making photographed examples very uncommon [16]Howson, 139. — however, the 6.5×52 1870/87/15 conversions would also appear in the conflict, albeit in Nationalist service.

Having been contracted in 1915 from American arms manufacturer Winchester Repeating Arms, the contract of 293,818 delivered 1895 Winchester lever action rifles chambered in Russia’s standard 7.62x54R cartridge marked one of two contracts for newly-manufactured arms in the United States, the other of which being contracts for Model 1891 Mosin-Nagant rifles with New England Westinghouse and Remington.[17]Luke Mercaldo, Adam Firestone, and Anthony Vanderlinden, Allied Rifle Contracts in America (Greensboro, NC: Wet Dog Publications, 2011), 65–88, 11-64. Russian use of the 1895 Winchester lever action, outfitted with a full, musket-length stock and half-handguard, stripper clip guides, and blade bayonet was extensive, tending to be favored by Latvian battalions, many of whom fought for the Bolsheviks during the later Civil War.[18]Mercaldo, Firestone, and Vanderlinden, Allied Rifle Contracts in America, 81. Despite chambering the standard 7.62x54R cartridge fed from a standard stripper clip, remaining Russian-contract Winchester 1895s were placed into reserve following the end of the Russian Civil War; 9,000 of which were sold to the Spanish Republic in 1936 as detailed above. Curiously, George Orwell implies that these rifles arrived or were issued without stripper clips, stating in Homage to Catalonia that “There were also a few Winchester rifles. These were nice to shoot with, but they were wildly inaccurate, and as their cartridges had no clips they could only be fired one shot at a time.”[19]George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (Boston, MA: Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015), 35. These rifles would have been among the first to arrive from Soviet Operation X shipments, and photos from late in 1936 and through 1937 distinctly represent these rifles in the thick of the fighting. Those that survived Spanish use would be offered on the American mail-order surplus firearm market by Sam Cummings’ Interarmco in the late 1950s and early 1960s; ad copy of the era definitively establishing their Spanish Civil War histories.

Imperial Russian purchasing commissions secured 600,000 rifles from Japan in 1915 and 1916, the majority of which being surplus Type 30 Arisaka “hook safety” rifles; though smaller numbers of improved Type 35 and modern Type 38 rifles were also acquired, all in 6.5×50 — along with this order, the Japanese included an additional 34,400 Type 38 rifles in 7x57mm from a defaulted Mexican contract.[20]Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight.” The Russians would go on to purchase a further 128,000 Type 30s and 38s from Great Britain in 1916, previously used as second-line rifles in order to free up Lee-Enfields for use in France.[21]Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight.” These rifles would have featured a series of “cancellation” markings in the form of the stacked cannonballs symbol of the Koishikawa District of the Tokyo Artillery Arsenal overstamped over the Imperial chrysanthemum; Type 30 rifles with Russian provenance may also feature a bent steel retaining clip securing the triggerguard magazine floorplate release. Ex-Japanese rifles would see extensive use in Russian service, and would consequently be scattered throughout the reaches of the old empire during the Russian Civil War — those that survived to be taken into Soviet inventory would be drawn from for sale to Spain in 1936, though the exact numbers of these are unknown. There is evidence of Spanish-used Type 30 and 38 rifles undergoing caliber conversion; in separate conversations with the author, researchers Fred Honeycutt and Francis C. Allan independently cite primary source documents as well as two surviving examples in the collection of the military museum in Toledo suggesting widespread conversion of Japanese rifles to the more-commonly available 7.92×57. Japanese rifles do not appear in many contemporary Republican photographs, though they are extensively represented in Nationalist surveys of captured small arms, and evidently survived in substantial enough numbers to have potentially been offered for limited sale on the American surplus market of the late 1950s.

Of the remaining types of nonstandard rifles sold by the Soviets to the Republican Spanish, the comparatively low numbers and varied types suggest that these rifles were miscellaneous variants used, inventoried, and stored following the end of the Russian Civil War. For instance, the number of Austro-Hungarian Mannlicher and German Mauser rifles cited by Howson are not specific to one individual model; all types in their respective chamberings are accounted for under Soviet categorization.[22]Howson, 138. Additionally, the number of .303 English Lee-Enfield and Canadian Ross Mk.III rifles enumerated in Howson’s list were likely sourced from ex-White Russian stocks, having fallen into Soviet hands following the defeat of the Whites in 1923, who had received them as aid earlier in the Russian Civil War during Allied intervention efforts.

These initial arms shipments, while desperately needed by Republican troops, largely came as an opportunity to offload obsolete and nonstandard weapons retained in Soviet inventory following the end of the Russian Civil War. The bulk of these shipments would continue through early 1937, when more modern Soviet weaponry would begin to end up in Republican hands.

Having largely exhausted stocks of obsolete, nonstandard weapons as sold to Republican purchasing commissions, Operation X records note the first shipments of standard Soviet small arms on January 16, 1937, with the arrival of 25,500 M91 Mosin-Nagant rifles and 20 million 7.62x54R cartridges on the ship Sac-2 and a further 24,580 rifles and 30 million cartridges on the Mar Blanco.[23]Howson, 285. Though in the process of being replaced in Soviet service by the more-modern M91/30 pattern, the vast numbers of M91 “Three-Line” rifles in reserve — ranging anywhere from worn examples dating from 1892 up to fairly new rifles produced at Tula and Izhevsk in 1926 — were a perfectly serviceable option for Republican issue.

The configuration and condition of the M91 rifles as shipped to Spain in early 1937 would have been varied; as with other types discussed above, many rifles saw hard service through the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War, the First World War, and the subsequent Russian Revolution and Civil War. The general characteristics of this rifle were an overall length of 51 ½ inches; weighing 9 ½ pounds; chambering the 7.62x54R cartridge in a five-round, stripper-clip fed magazine; having a full-length stock and handguard; making use of a socket-style spike bayonet, and incorporating the Konovalov rear sight graduated out to 3200 arshin, with a barleycorn front sight blade.[24]Luke Mercaldo, Adam Firestone, and Anthony Vanderlinden, Allied Rifle Contracts in America (Greensboro, NC: Wet Dog Publications, 2011), 54. Through their production life, the “Three-Line” M91 rifle would be manufactured domestically by Russian arsenals (both under Imperial and later Soviet direction) at Tula, Izhevsk, and Sestroryetsk, and under contract abroad early in production by Chatellerault in France, and by New England Westinghouse and Remington Arms in the United States during the First World War.[25]Mercaldo, Firestone, and Vanderlinden, 25-40.

The Spanish Republic would receive Soviet shipments of the “Three-Line” M91 rifle definitively totalling 104,630 rifles, with a supplemental 25,000 potentially also delivered.[26]Howson, 285-95. M91 Mosin-Nagant rifles would make up the bulk of delivered small arms from January to August of 1937, after which Soviet deliveries to the Republic would be made up of new production M91/30 variants of the Mosin-Nagant. However, M91s would be numerous in Republican use, as the Soviet Union was not the only country to provide the old “Three-Line” rifles — both Poland and Mexico would also sell them to Republican purchasing commissions, albeit in lesser numbers.

Soviet deliveries of M91/30 Mosin-Nagant rifles would begin alongside that of the final shipment of M91s in August of 1937 aboard the Cabo San Augustin, with 10,450 accompanying the 39,550 “Three-Line” rifles and 52,696,000 rounds of 7.62x54R also listed on the Operation X shipping manifests for this voyage.[27]Howson, 293-94. The M91/30 rifle was the Soviet Union’s most modern update of the Mosin-Nagant action, shortened to an overall length of 48 ½ inches, weighing slightly less than 9 pounds, and equipped with an updated rear tangent sight graduated up to 2000 meters and an easier-to-acquire globe front sight, this new weapon was the Red Army’s most modern bolt action infantry rifle.[28]Aleksandr Sergeyevich Yushchenko, Vintovka obraztsa 1891/1930 g. i yeye raznovidnosti. Production of the M91/30 would be undertaken at Tula and Izhevsk.

Though the majority of rifles supplied by the Soviet Union were obsolete weapons held in reserve following inventory efforts following the Russian Civil War, the supply of M91/30 Mosin-Nagant rifles was unique in that they were new production rifles — many M91/30s with Spanish Civil War provenance display 1936 and 1937 dates of production. Shipments of these rifles continued through 1937 and 1938, with a total deliveries reaching 112,050 rifles along with bayonets and hundreds of millions of rounds of ammunition.[29]Howson, 296-300. These rifles regularly appear in frontline photographs, generally adapted to use domestic Mauser slings with the addition of a pair of bent wire sling swivels, and are also frequently detailed in Nationalist captured weapon documentation.

An additional curiosity is the Spanish Civil War provenance of the so-called “Stable rifles,” a limited production trials rifle variant of the M91/30 developed in the mid-1930s. These rifles differed from standard M91/30s in that they featured a Mauser-style front band, blade bayonet, and a set of winged sight protectors in lieu of the M91/30’s globe.[30]Yushchenko, Vintovka obraztsa 1891/1930 g. i yeye raznovidnosti. In the collector’s market, these rifles frequently appear with signs of Spanish issue and postwar Nationalist inventory and arsenal refurbishment; though no examples have turned up in wartime photos. Curiously, a possible hint to their transport is recorded in Operation X shipping manifests, as Howson cites a quantity of 8,400 “Rifles M34” recorded alongside 26,500 standard M91/30 Mosin-Nagants in the cargo of the Bonafacio, arriving in a Republican port on February 7, 1938.[31]Howson, 298. However, this quantity exceeds that of the estimated production of the Stable rifles, of which 5,000 are thought to have been produced at Tula in the 1936-1937 timeframe.[32]Yushchenko, Vintovka obraztsa 1891/1930 g. i yeye raznovidnosti. Whatever the status of these “Rifles M34,” they certainly were not standard M91/30 rifles, and further research is needed to definitively establish their identity.

Rifles from Polish Sources: Secondhand arms from SEPEWE

Having gained nationality in the political tumult following the First World War and consequently caught up in the Polish-Soviet War of 1920, the military forces of the Second Polish Republic were armed with numerous rifle types left over from Imperial German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian service. Efforts to standardize on rifles chambered in 7.92×57 in the late 1920s resulted in the gradual disposal of older, nonstandard types in both military and border guard service — foreign weapons not conforming to this standard were collected, refurbished, and held in reserve in a number of military arsenals beginning in 1928.[33]Piotr Kozłowski, “Uzbrojenie I Wyposażenie Małopolskiego Inspektoratu Okręgowego Sg W Przemyślu,”Biuletyn Centralnego Ośrodka Szkolenia no. 29 (2004), 53–5. Among these nonstandard weapons were French Lebel and Berthier rifles and carbines, varieties of Austro-Hungarian Mannlicher straight-pull rifles in 8x50R, old German 1888 Commission rifles, English P14 Enfields in .303, and worn M1891 “Three-Line’ rifles, potentially candidates for conversion to the Polish 7.92×57 caliber wz.91/98/28 pattern.[34]Tomasz Juszkiewicz, “Uzbrojenie W Karabiny I Karabinki Powtarzalne, Korpusu Ochrony Pogranicza W Latach 1924-39.” Biuletyn Centralnego Ośrodka Szkolenia 1/98 (1998), 55-69.[35]Kozłowski, 54. These rifles would largely remain in Polish reserve until representatives of the Spanish Republic would approach the Polish government through intermediaries in 1936.

Interwar Polish commercial interests in foreign military contracts were largely brokered through SEPEWE, an ostensibly-private (though in reality, government-sanctioned) arms export syndicate. Sales to Republican Spain began in the autumn of 1936; as the Polish government was officially subject to an arms embargo against both factions in the Spanish conflict (an agreement that it did not abide to, selling to both throughout the war), traffic of arms to Republican ports was necessary to disguise through a series of assumed destinations.[36]Marek Piotr Deszczyński, “Eksport Polskiego Sprzętu Wojskowego Do Hiszpanii Podczas Wojny Domowej 1936-1939.” Kwartalnik Historyczny 104, no. 1 (1997), 49. Like initial Soviet shipments, SEPEWE first brokered a series of sales of obsolete, nonstandard, and/or unserviceable weapons to Republican purchasing agents, before later supplying a number of modern, standard-issue domestic or license-built weapons — curious, as Poland was in the midst of a military modernization and rearmament program and somewhat lacking for modern arms for its own use.[37]Howson, 259-77.

Citing interwar SEPEWE export records, Polish researcher Marek Piotr Deszczyński notes the dizzying variety of covers provided to arms exports destined for Republican Spain — shipments from 1936 through 1938 ostensibly delivered to ports of destination in France, Mexico, Uruguay, Greece, Haiti, Venezuela, and Peru.[38]Marek Piotr Deszczyński, “Polski eksport sprzętu wojskowego w okresie międzywojennym (Zarys problematyki).” Przegląd Historyczny, no. 85/1-2 (1994), 106-10. Deszczyński cites the total types and amounts of rifles exported to the Republican Spanish by SEPEWE during this period as numbering up to 88,001 new-production wz.29 Mauser carbines; 24,500 wz.98a Mauser rifles; 50,000 Berthier rifles and carbines; a mixed shipment of 7,000 Mannlicher M.88, M.88/90, and M.95 rifles, and 5,000 Mannlicher M.95 rifles.[39]Deszczyński, 106-10.

However, this data does not fully correspond with that which Howson provides in his analysis of individual shipping manifests; establishing that quantities of Polish small arms to arrive in Spain only during 1936 and 1937 would total 25,100 new-production wz.29 Mauser carbines; 37,400 Berthier rifles; two mixed shipments of old Austro-Hungarian M.88, M.88/90, and M.95 Mannlichers totalling 12,000 rifles; 10,000 Mannlicher M.95 carbines along with 10,000 rifles; around 2,000 1888 Commission rifles; 2,930 “Russian rifles and spare parts,” and a further 10,000 otherwise-unidentified 8mm rifles.[40]Howson, 259-77.

As the only modern rifles supplied to the Spanish Republic by Poland, the wz.29 Mauser was a domestically-produced short rifle chambered in 7.92×57, with an overall length of 43.4 inches and weighing 9 pounds unloaded.[41]Olson, 187. Generally, the receiver rings of wz.29 rifles would feature a Polish national eagle over a dated manufacturer’s marking, either “P.F.K. WARSZAWA” or “F.B. RADOM,” but most rifles with known Spanish provenance lack these crests. However, there is the question of whether the rifles provided to the Spanish Republic originally featured them, or if they were supplied “sanitized.” Interestingly, Nationalist documentation seems to suggest that wz.29 and other Mauser rifles supplied by Poland indeed featured the national crest — granted, this may have been only of note due to most captured examples appearing without them. Regardless, most wz.29 rifles on the collector’s market lack Polish crests.

In addition to wz. 29 models, the older wz. 98a was also supplied in quantity to Republican forces. This rifle was produced on Gewehr 98 tooling from the former Danzig arsenal, differing only from the older pattern in its incorporation of a flat tangent rear sight instead of the lange vizier pattern, and Polish markings. Additionally supplied were a number of Polish-produced Model K.98 carbines; nearly identical to the Kar.98az produced by Imperial Germany save for an updated and strengthened stacking hook. Examples of each appear in wartime Republican photos, but not as frequently or as distinctively as the wz.29 models.

Though French-made Berthier rifles supplied by the Soviets were mainly of the three-shot Mle. 07/15 pattern, numbers supplied by the Polish were of multiple variants; Tomasz Juszkiewicz cites three-shot Mle. 92 carbines and Mle.07/15 rifles as well as updated five-shot Mle. 92/16 carbines and Mle. 07/15-M16 rifles in prewar Polish service.[42]Juszkiewicz, 66-8. As these rifles were drawn from Polish reserve stockpiles, it is likely that no attempt was made to consistently issue like models — indeed, the above photo shows multiple Berthier variants within the same unit.

Polish issue of inherited ex-Austro-Hungarian arms was varied, with numbers of earlier M.88 and M.88/90 straight-pull rifles less than those of the more modern M.95s. Incorporating a wedge-locking, straight-pull action, M.88s and M.88/90 rifles (the latter updated to use Austria-Hungary’s smokeless 8x50R loading), fed from an innovative five-round en-bloc packet; revolutionary for the 1880s, this design had been largely surpassed by Mauser action rifles and served as a frontline, secondary standard rifle during the First World War.[43]Paul S. Scarlata, Mannlicher Military Rifles (Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray Publishers, 2004), 51-64. These rifles, while common in the reaches of the old Autro-Hungarian empire, were far from modern, and the Poles elected to keep them in reserve rather than issue them; and naturally, the opportunity to offload them onto the Republican Spanish proved to be just the thing to clear them out of inventory.

Ferdinand Mannlicher’s updated straight-pull design, the M.95, was adopted for Austro-Hungarian service in 1896 following a series of trials exploring innovations on his earlier designs. Produced both at OEWG Steyr and at Budapest in Hungary, the M.95 rifle had an overall length of 50.1 inches and weighed 8.3 pounds, and incorporating a rear sight graduated up to 2600 schritt, these rifles still chambered 8x50R but fed from an improved en-bloc packet. These rifles served as the standard arm of the Austro-Hungarian empire throughout the First World War, seeing service against both the Italians and the Russians.[44]Scarlata, 74-86. Poland inherited large numbers of these rifles following independence and the Polish-Soviet War, electing to export them from reserve stocks throughout the 1930s, providing numbers to Bulgaria and Romania in 1932, China and Abyssinia in 1934, and Hungary in 1936 in addition to those sold to the Spanish Republicans.[45]Deszczyński, “Polski eksport sprzętu wojskowego w okresie międzywojennym (Zarys problematyki),” 105–7.

A carbine variant was also developed and produced, though Polish-supplied M.95 carbines appear to have been domestically shortened from full-length long rifles, incorporating renumbered rifle-length rear sights and underslung sling swivels — though some surviving examples appear to have originally featured a bottom swivel repurposed as a wrist swivel, later plugged and reverted to the original underslung configuration. Note these features on the above carbine.

Developed in response to the French 1886 Lebel rifle and its 8mm smokeless cartridge, the German 1888 Commission rifle used a split-bridge Schlegelmilch action and incorporated a Mannlicher-style en-bloc clip, originally chambering the .318 bottlenose M/88 7.92×57 cartridge developed alongside it, though later updated to the .323 S Patrone spitzer loading in 1905.[46]Olson, 40-2. Despite military adoption of the Mauser-designed Gewehr 98, the 1888 Commission rifles would remain in inventory and conversions to accommodate the new ammunition and stripper clip loading would result in the 1888/05 variant; these rifles would serve as German reserve weapons throughout the First World War. The relatively low number retained in postwar Polish service and subsequently provided to the Republican Spanish makes photographic evidence scarce; though limited, frontline use of the 1888 Commission rifle was surely superior to that of older, single-shot blackpowder rifles dug out of Soviet reserve stocks.

Rifles from Mexican Sources: Modern Mausers, Ammunition, and the Allure of the “Mexicanski” Mosin-Nagants

Mexican aid to the Spanish Republic came early, initially in the form of 20,000 domestically-produced Mauser 1910 rifles and 20 million rounds of 7×57 ammunition as a gesture of goodwill from President Lázaro Cárdenas aboard the Magellenes in September of 1936.[47]Howson. 103. In addition to these rifles, a reported 7,000 others along with 10 million cartridges would arrive through late 1936 and early 1937.[48]Mario Ojeda Revah, Mexico and the Spanish Civil War (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2015), 114. Despite being based on the general pattern of the Spanish 1893 Mauser, these rifles were built on the improved Mauser 98 action; however, there was no practical difference in use beyond that of the standard Spanish rifle, including chambering the same 7×57 round. In appearance, the two rifles are near identical, making identification very difficult in period photographs.

In terms of contemporary discussion, there is little comment on the quality or issue of Mexican 1910 pattern Mausers — Mexican researcher Mario Ojeda Revah only cites Manchester Guardian correspondent Frank Jellinek qualifying them as “Excellent, lighter than the Spanish Mauser type…”[49]Revah, 110. — dialogue on the quality of Mexican produced 7×57 Mauser ammunition is better known due to George Orwell’s praise of it in comparison to poor quality Spanish ammunition. In reference to the issue of ammunition among the POUM militias, he states that:

“Ammunition was so scarce that each man entering the line was only issued with fifty rounds, and most of it was exceedingly bad. The Spanish-made cartridges were all refills and would jam even the best rifles. The Mexican cartridges were better and were therefore reserved for the machine-guns. Best of all was the German-made ammunition, but as this came only from prisoners and deserters there was not much of it. I always kept a clip of German or Mexican ammunition in my pocket for use in an emergency.”[50]Orwell, 35-6.

Mexican domestic production of the 7×57 Mauser cartridge began in 1906 at Fabrica Nacional de Cartouches following military commission review of cartridge production facilities and methods at Winchester and Union Metallic Cartridge Co. in the United States, and those of D.W.M. in Germany.[51]James B. Hughes, Mexican Military Arms: The Cartridge Period, 1866-1967 (Houston, TX: Deep River Armory, 1968), 120.

Supply of domestically produced rifles and ammunition in the standard form and caliber to the Spanish Republicans served as both a logistically and ideologically considerate gesture; as initial shipments of both were done at no cost, though the Mexican government eventually consented to accept a payment of 3,500,000 pesos for them.[52]Howson, 103.

An enduring curiosity of Mexican aid to the Spanish Republic is that of the so-called “Mexicanski” Mosin-Nagant rifles; U.S.-manufactured M91s allegedly supplied to members of the International Brigades from Mexican-marked crates. Cecil Eby relates the issue of these rifles in Comrades and Commissars: The Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War, stating:

“In the chill February evening they lined up behind a supply truck and unloaded heavy boxes about the size of coffins. Breaking them open, they found new bolt action rifles, each wrapped in Mexico City newspapers and oozing cosmoline. With each came a small cloth bag stuffed with cleaning brushes and small tools but no rags. ‘Clean them,’ came the order. ‘With what?’ came a plaintive voice. ‘Use your shirttails,’ barked Seacord. The rifles were Remingtons, some barrels stamped with the Czarist double-eagle, others with the Soviet hammer and sickle. The latter were seven centimetres shorter and a few ounces lighter, but their bolts were prone to jam when overheated. (Some rifles were stamped ‘Made in Connecticut.’) The men nicknamed their rifles ‘Mexicanskis’ and the story passed into local folklore that they had been manufactured in the United States, sent to the Czar in 1914, copied by Bolshevik artisans, sold to Mexico for revolutionary work and then donated to the Spanish Republic.”[53]Cecil D.Eby, Comrades and Commissars: The Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007), 47.

Note that Eby reports the simultaneous issue of rifles marked with the “Soviet hammer and sickle,” and “seven centimeters shorter and a few ounces lighter” in comparison to the American-manufactured M91 “Three-Line” rifles; this no doubt erroneously refers to M91/30 rifles, which could not possibly have been “copied by Bolshevik artisans” nor sold to Mexico.

However, at least one instance of attempted Mexican supply of American-produced Mosin-Nagants (as well as Winchester Model of 1917 rifles) is documented in the manifest of the Mar Cantabrico, a Republican vessel bound from Veracruz but intercepted before reaching a friendly port by the Nationalist cruiser Canaris on March 8, 1937. Among the military cargo were 990 Remington-manufactured M91 Mosin-Nagants and 967 Winchester Model of 1917 “Enfield” rifles, accompanied by 376,000 rounds of Winchester-produced 7.62x54R, 2,249,000 rounds of mixed-manufacture 30.06 (1,378,200 in bandoliers), 36,000 rounds of Winchester .303 British, and 9,428,000 rounds of 7×57 Mauser.[54]Xosé Manuel Suárez, “La Tragedia Del Mar Cantábrico y Otros Apresamientos Navales En La Guerra Civil” (Drassana no. 18, 2010), 76. Though this instance is not fully indicative of widespread Mexican supply of American-produced M91 Mosin-Nagants, the proximity of the Lincoln Battalion’s apparent issue of Remington-manufactured examples and the Mar Cantabrico’s capture at sea suggests that many Remington or New England Westinghouse rifles in Republican hands in early 1937 may likely have had a Mexican source.

Minor Sources: Paraguay, Estonia, Czechoslovakia, Belgium

Paraguay

According to Gerald Howson, Republican purchasing agents sourced a number of surplus weapons from Paraguay. These weapons, largely in poor condition as a result of hard service in the 1932-1935 Gran Chaco War, were of both Paraguayan and captured Bolivian origin. Among the cargo of the Ploubazlanec — which had arrived at port in Tallinn, Estonia on September 25, 1937 in order to take on Paraguayan arms shipped from Buenos Aires by way of Poland— were 7,119 Mauser rifles chambered in 7.65×53, the standard caliber of both belligerent nations of the Gran Chaco.[55]Howson, 276.

Initially purchasing export pattern Mauser 1898s from DWM in 1907, Paraguay contracted further numbers of an updated rifle pattern in 1927 from Oviedo in Spain following increased tensions with Bolivia.[56]Paul S. Scarlata, “La Guerra Del Chaco: The Bloodiest Latin American War of the 20th Century: Part I.” Shotgun News, April 20, 2014. When fighting would commence in the Gran Chaco in 1932, these rifles evidently did not give a good account of themselves; compounding issues with poor-quality Belgian Caulille powder used in the production of 7.65×53 ammunition would result in receiver failures, leading Paraguayan troops to nickname them “mata paraguayos” — “Paraguayan killers” — and exchange them for the Czechoslovakian-produced Vz.24 rifles of their Bolivian adversaries whenever possible.[57]Bernardo Neri Farina, José Bozzano y La Guerra Del Material (Asunción, Paraguay: El Lector, 2011). Examples of Paraguayan 1927 rifles appear in post-Spanish Civil War Nationalist inventories; no accounts of similar failures are documented in this context, though examples with Spanish provenance seem to have been curiously converted to 7.92×57.

In 1926, Bolivia contracted for 36,000 Czechoslovakian-produced Vz.24 rifles and 6,000 carbines, a contract brokered through English firm Vickers-Armstrong as part of military modernization efforts.[58]Scarlata, “La Guerra Del Chaco: The Bloodiest Latin American War of the 20th Century: Part I.” Further rifle contracts with Ceskoslovenska Zbrojovka Brno would number up to 101,000 from 1928 to 1938, with post-Chaco War purchases aimed to replace weapons lost in the conflict.[59]Ball, 59-60. Other than displaying the Bolivian national crest on the receiver ring and the 7.65×53 chambering, these rifles were identical to the Vz.24 rifles of the Czechoslovakian military; with an overall length of 43.3 inches and an unloaded weight of 9.2 pounds. In Spanish use, postwar documentation suggests that these rifles remained in their original chambering, unlike the Paraguayan 1927 Mausers.

Estonia

Though Howson cites a number of voyages from Tallinn under SEPEWE direction — notably, that of the Ploubazlanec — he does not discuss any direct Estonian support. However, Estonian researcher Toe Nõmm cites limited numbers of small arms sales to the Spanish Republicans, numbering a total of 725 rifles; 475 of which were “old German rifles” used by the Prison Service, and the remaining 250 being .303 P14 Enfield rifles.[60]Toe Nõmm, “Eesti Sõjapüssid 1918–1940” (Laidoneri Muuseumi Aastaraamat, 2005), 46. In addition to these, Estonia sold the Republicans 11.4 million scrap 7.62x54R cartridges originally purchased from Finland, as well as quantities of 8mm Lebel cartridges in the low millions.[61] Nõmm, 46. Though scarcely a major contribution, Nõmm does provide evidence that Estonia forwarded at least some material support to the Republic.

Czechoslovakia

In the efforts to secure arms abroad, Republican ambassador Luis Jiménez de Asúa was able to purchase quantities of weapons and ammunition in Prague in November of 1936; owing to delays and Soviet obstinance, this material would not be shipped until March and April of 1938.[62]Howson, 144. Consequently, as shipping was arranged by Soviet agents, these weapons appear in Soviet “Operation X” manifests. Among them were 50,000 Vz.24 rifles in 7.92×57 sold directly from Czechoslovakian military reserves.[63]Howson, 298. Unlike many wz.29 rifles sold from Polish stocks, these rifles retain either their “lion rampant” or identifying “ČESKOSLOVENSKÁ ZBROJOVKA BRNO” crests, but seem to have had Czech military acceptance marks on the left wall of the receiver ring stippled over.[64]Ball, 116. These rifles were shipped alongside Czech-made machine guns and ammunition, totalling 474,200,00 rounds of new Czech manufacture and 30 million of older French 7.92×57 ammunition.[65]Howson, 298-300.

Belgium

Republican attempts to source arms in Belgium in 1936 were largely thwarted by a royal decree banning the export of arms to Spain’s belligerent factions on August 19 of that year; effectively nullifying the purchase of a “grand lot” of arms including 50,000 new Mauser rifles produced by Fabrique Nationale and 15 million cartridges, 30,000 old Mausers and eight million cartridges, and 16,000 Mannlicher rifles.[66]Howson, 86. However, at least one small arms shipment evaded internment by Belgian authorities in autumn 1936 after which 6,000 Mauser rifles, 100 machine-guns, and 500,000 cartridges were transferred from the Belgian coaster Alice to the Basque vessel Iciar en route to Bilbao.[67]Howson, 87. This shipment ostensibly was able to pass due to the Alice’s “cover” destination of England, with the cargo allegedly being returned as “unsaleable” to British arms dealers. This enterprise would have remained undetected if not for the vessel’s collision with the Royal Scot at the neck of the Thames estuary and the subsequent discovery of the transfer of arms to the Spanish vessel.[68]Howson, 87. Despite the lack of detailed descriptions of this cargo, postwar Nationalist inventories note captured examples of the Belgian 1889 Mauser, the first adopted smokeless Mauser military rifle, additionally the first to be chambered in 7.65×53.[69]Ball, 22-9.

Capture, Display, and Refurbishment

Following Republican defeats through 1937 and 1938, collection and refurbished of captured war material by Nationalist forces resulted in large numbers of these arms being reissued, resulting in the production of a series of documents for the issue and use of weapons of foreign origin formerly in use by the Ejército Popular or regional/political militia units. The first of these, produced in 1938 by the Jefatura De Movilización Instrucción y Recuperación and titled Armas Automáticas y Fusiles De Repetición, detailed the operation of a number of captured automatic weapons and infantry rifles. Among the latter are the Mannlicher M.95 family; the Mosin-Nagant (in both M91 and M91/30 form); Polish wz.29 and K.98 Mausers, alongside Imperial German Kar. 98a carbines; the Japanese Type 35 rifle; the Czechoslovakian Vz.24, and the French Berthier Mle.07/15-M16 variant — which the text refers to as the “Saint Etienne” rifle.[70]Armas Automáticas y Fusiles de Repetición (Burgos: Jefatura De Movilización Instrucción Y Recuperación, 1938), 85-107. This text, more accessible than surviving examples of the significantly-more-rare Republican instructional documentation, appears to have been among the first efforts to catalog captured foreign weapons, an undertaking that would take on a greater propaganda importance in the autumn of the same year.

On August 29, 1938, the Nationalist Servicio de Recuperación de Material de Guerra would organize a “captured enemy material exposition” in the town of San Sebastián, displaying a series of captured artillery pieces, armored vehicles, aircraft, munitions, and infantry small arms in that city’s Gran Kursaal exhibition venue. Framed as an exposé of international conspiracy against the people of Spain, Nationalist commentary on the selection of foreign-supplied armaments was detailed in a series of published photographic programs; modern reproductions and synthesis of these materials reprint images from the exhibition as well as notes on the operation and quality of foreign arms.

Commentary on rifles of German, Belgian, and some of Polish origin noted the age of many of them; but the modernity and ease of operation of captured wz.29 and Czech Vz.24 rifles was praised.[71]José María Manrique García, and Lucas Molina Franco. Arms of the Spanish Republic: A Nationalist Overview, 1938 (AFV Collection, no. 3. Valladolid, Spain: AF Ediciones, 2007), 69. All examined Russian rifles, of either M91 “Three-Line” or modern M91/30 construction were qualified as “good and reliable, and although looking obsolete…gave a good account of themselves in the conflict.”[72]Manrique García and Franco, 69. As expected, Mexican Mauser rifles were noted for their similarity to Spanish models; and interestingly, commentary on captured Japanese rifles noted that some of them had undergone conversion to 7.92×57.[73]Manrique García and Franco, 69. Evidently, Austro-Hungarian Mannlicher rifles “always gave trouble with the ammunition,” and featured “excessive erosion of the barrels,” giving an overall impression of unreliability.[74]Manrique García and Franco, 69. American and English weapons were seemingly reliable weapons, some of the former are noted as having “come via Mexico,” potentially in reference to American-contracted M91 Mosin-Nagant rifles; and French weapons, largely inherited from ex-Imperial Russian stocks, were “obsolete and little effective.”[75]Manrique García and Franco, 69.

Following the Republic’s defeat in 1939, Nationalist efforts to fully survey captured small arms with the aim of determining origin and operation of these weapons resulted in a survey of inventoried examples titled Prontuario De Armamento, compiled by artillery captain Mariano Villoslada Miñon. This text, numbering 351 pages, is a complete index of Republican infantry arms, surveying both domestic and foreign-produced weapons, including photographs and functional descriptions, many of which appear throughout this article.

As nonstandard weapons, foreign rifles used by the defeated Republicans would be inventoried by the Servicio de Recuperación de Material de Guerra and placed into military reserves; evidence suggesting that some more-modern rifles would undergo refurbishment and repair programs. These weapons would remain in postwar stockpiles until sale on the American sporting market through Sam Cumming’s Interarmco in the late 1950s.

“Shootin’ Goodies from General Franco:” Importation and Commercial Sale of Spanish Civil War Surplus

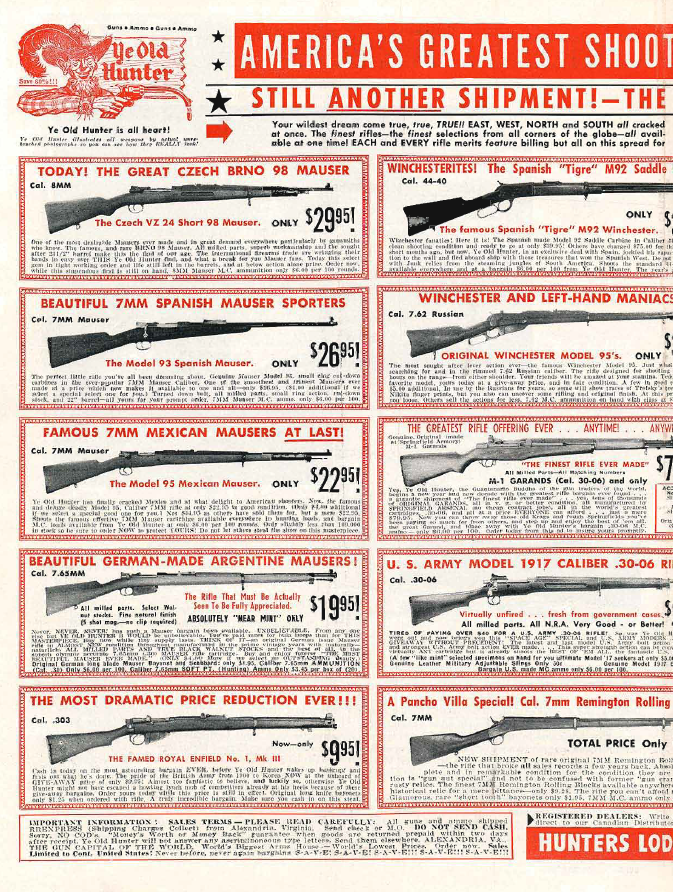

In the years following World War Two, the development of a surplus arms market arose from the worldwide obsolescence of older military small arms. In the United States, chief among the surplus trade was Sam Cummings, operator and founder of Interarmco in Alexandria, Virginia. Cummings’ efforts to purchase stocks of surplus military weapons across the globe to offer on the American commercial market through mail-order retail outlets would see him broker deals with a variety of governments, among them the Franco regime.[76]Patrick Brogan and Albert Zarca, Deadly Business: Sam Cummings, Interarms, and the Arms Trade (New York: Norton, 1983), 126-27. Weapons with possible Spanish origins would begin appearing in ad copy for Interarmco’s “Ye Olde Hunter” outlet in 1956; arms with definite Spanish Civil War histories would be advertised in 1957.

A canvas of contemporary ad copy in Guns magazine reveals a number of Spanish Civil War rifles sold through Ye Olde Hunter and the rival Golden State Arms Corporation, the first major offerings occurring in the spring of 1957 with “confiscated ‘MN’ Russian” M91/30s and “French Foreign Legion” Berthier Mle. 07/15-M16 rifles.[77]Golden State Arms. Corp, Advertisement. Guns Magazine , May 1957, 2. More rifles would be offered through Interarms mail-order outlets and affiliated vendors throughout the late 1950s, with (at various times) Russian-contract Winchester 1895s (curiously identified in period advertisements as having come from Spain); M91 and M91/30 Mosin-Nagants; M.88, M.88/90, and M.95 Mannlichers; Polish K.98 and wz.29 Mausers; Vetterli-Vitali M1870/87 and 6.5×52 M1870/87/15 rifles; French Gras and Berthier rifles, and domestic Spanish 1893 and 1916 Mausers.

In most cases, Cummings’ typically flippant ad copy does not refer to the sources of the weapons, but that of partnered retailers occasionally does; notable instances early in the first stage of imports include the above Martin B. Retting, Inc. advertisement from the March 1957 issue of Guns magazine, and a Ma Hunter ad from the June 1957 issue of the same magazine running with the tagline “Look what I got from General Franco, shootin’ goodies!”[78]Ma Hunter, Advertisement, Guns Magazine, June 1957, 56. Though most Spanish weapons seem to have been offered through Interarmco’s “Ye Olde Hunter” mail order operations, they seem to have offered items of lesser quality or quantity through their Potomac Arms Corporation outlet in August of 1960, with 7.62x54R Winchester 1895, Spanish “El Tigre” Winchester 1892-copy, and Czech Vz.24, barreled actions for sale, as well as a limited number of Japanese Type 30 rifles.[79]Potomac Arms Corp., Advertisement. Guns Magazine, October 1960, 41. These offers appear alongside other weapons of Spanish origin in Ye Olde Hunter copy earlier in the same issue, pictured above.

Brogan and Zarca state that Cummings made two purchases of the obsolete arms stockpiles in Spain; their assertion that these purchases took place first in 1959-1960, and again in 1965-1966 seems to defy the offerings of weapons with an undeniably Spanish origin throughout the late 1950s. Examining Ye Olde Hunter and Potomac Arms advertisements from the 1965-1966 era shows few rifles dating to the period of the Spanish Civil War; circumstantial evidence suggests that it is more likely that the first sale occurred in 1955-1956, and the second in the 1959-1960 timeframe.[80]Brogan and Zarca, 126. Regardless, they cite both sales as totalling over one million weapons and nearly 250 million rounds of ammunition of various calibers.[81]Brogan and Zarca, 106.

Identifying Features of Spanish Civil War Small Arms

As the Republic sourced its weapons from across the globe in varying states of serviceability from prior use, many of these small arms bear more easily-identifiable signs of their countries of initial origin. However, a number of features and markings have been recorded that appear unique to weapons that saw service in the Spanish Civil War. Not all of these features are specific to weapons in the service of the Republic; rather, many of them appear to have been applied postwar in Nationalist storage or rebuild programs. One such example is the above cartouche, a uniquely-Spanish mark that seems to have been applied to rifles present in postwar inventory — nonspecific to Republican or Nationalist origin, the exact meaning of this mark is as of yet unknown, though some researchers have suggested that it denotes storage and refurbishment at “Maestranza y Parque de Artillería,” facility number eight.

Additionally, weapons imported from Spain by Interarmco bear a series of import marks determining country of origin in the form of capital, serif letters. For example, Spanish Civil War Mosin-Nagant rifles may either bear a “MADE IN USSR” or an erroneous “MADE IN URRS” stamp in this style; many French weapons sold to the Republicans from both Polish and ex-Imperial Russian stocks will bear a “MADE IN FRANCE” mark; Italian rifles (those used by both Republican and Nationalist forces) will read “MADE IN ITALY,” and ex-Austro-Hungarian Mannlicher rifles will be stamped “MADE IN AUSTRIA.”

Curiously, Polish Mauser rifles do not feature this type of marking; generally having a scrubbed receiver ring and featuring a large “A” enclosed in a circle on the left side of the stock. In collector’s circles, this marking is often described as signifying Anarchist issue, but this is completely without evidence. Additionally, Polish Mausers may feature a small “8mm” caliber stamp applied on the barrel upon import by Interarmco. Czech Vz.24 rifles also feature this importer-applied caliber mark, as well as having stippled-over Czechoslovakian acceptance marks as discussed in prior sections.

Unique to Spanish-used Mosin-Nagant rifles is the addition of a pair of wire-loop sling swivels in the sling-slot escutcheons; these differ from Finnish sling swivels, which are attached with screws. Spanish-used Mosin-Nagants may also feature rough domestic replacement stocks that generally do not feature metal handguard reinforcements. As a large portion of 1936 and 1937-dated M91/30 rifles were diverted to Spain as part of “Operation X” sales, these dates will be commonly encountered; though earlier dates may also appear. To date, no M91/30 rifles dated after 1937 have proven to be definitively issued to the Republic.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dave Carlson for directing me to valuable primary source documents, to Othais McCarthy for the use of the Spanish “MP8” cartouche image, and to Fred Honeycutt and Francis Allan for information regarding Spanish Civil War use of Japanese rifles.

A lot of the groundwork for this article was laid by Gunboards member Ithilsdorf and his information webpage on Spanish Civil War Mosin-Nagant research. Much of his research and survey data helped to establish provenance for other types of rifles used in the conflict.

All images were used as per the terms and conditions of their copyright holders, either attributed within the image, or shared via Creative Commons license. Photographs attributed to Constantino Suarez are sourced via a collection of his images, Constantino Suárez, fotógrafo: 1920-1937, available online courtesy of the Museum of the Asturian People.

is the pseudonym of a recent college graduate interested in the history and mechanics of 19th and 20th century military small arms, particularly those used in lesser-known conflicts.

References

| ↑1 | Ludwig Olson, Mauser Bolt Rifles (Montezuma, IA: Brownell & Son, 2002), 65-7. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Olson, 73. |

| ↑3 | Robert Ball, Mauser Military Rifles of the World (Iola, WI: F + W Media, 2011), 353. |

| ↑4 | Burnett Bolloten, The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 330. |

| ↑5 | Bolloten, 145–58. |

| ↑6 | Stanley Payne, The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), 141–44. |

| ↑7 | John Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight,” Guns Magazine, April 2005 |

| ↑8 | Payne, 156–57. |

| ↑9 | Gerald Howson, Arms for Spain (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), 136-39, 278-85. |

| ↑10, ↑22 | Howson, 138. |

| ↑11, ↑13, ↑15, ↑20, ↑21 | Sheehan, “Arming Ivan, Part II: The Bear Begs, Borrows, and Buys Guns to Stay in the Fight.” |

| ↑12, ↑14, ↑16 | Howson, 139. |

| ↑17 | Luke Mercaldo, Adam Firestone, and Anthony Vanderlinden, Allied Rifle Contracts in America (Greensboro, NC: Wet Dog Publications, 2011), 65–88, 11-64. |

| ↑18 | Mercaldo, Firestone, and Vanderlinden, Allied Rifle Contracts in America, 81. |

| ↑19 | George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (Boston, MA: Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015), 35. |

| ↑23 | Howson, 285. |

| ↑24 | Luke Mercaldo, Adam Firestone, and Anthony Vanderlinden, Allied Rifle Contracts in America (Greensboro, NC: Wet Dog Publications, 2011), 54. |

| ↑25 | Mercaldo, Firestone, and Vanderlinden, 25-40. |

| ↑26 | Howson, 285-95. |

| ↑27 | Howson, 293-94. |

| ↑28 | Aleksandr Sergeyevich Yushchenko, Vintovka obraztsa 1891/1930 g. i yeye raznovidnosti. |

| ↑29 | Howson, 296-300. |

| ↑30, ↑32 | Yushchenko, Vintovka obraztsa 1891/1930 g. i yeye raznovidnosti. |

| ↑31, ↑63 | Howson, 298. |

| ↑33 | Piotr Kozłowski, “Uzbrojenie I Wyposażenie Małopolskiego Inspektoratu Okręgowego Sg W Przemyślu,”Biuletyn Centralnego Ośrodka Szkolenia no. 29 (2004), 53–5. |

| ↑34 | Tomasz Juszkiewicz, “Uzbrojenie W Karabiny I Karabinki Powtarzalne, Korpusu Ochrony Pogranicza W Latach 1924-39.” Biuletyn Centralnego Ośrodka Szkolenia 1/98 (1998), 55-69. |

| ↑35 | Kozłowski, 54. |

| ↑36 | Marek Piotr Deszczyński, “Eksport Polskiego Sprzętu Wojskowego Do Hiszpanii Podczas Wojny Domowej 1936-1939.” Kwartalnik Historyczny 104, no. 1 (1997), 49. |

| ↑37, ↑40 | Howson, 259-77. |

| ↑38 | Marek Piotr Deszczyński, “Polski eksport sprzętu wojskowego w okresie międzywojennym (Zarys problematyki).” Przegląd Historyczny, no. 85/1-2 (1994), 106-10. |

| ↑39 | Deszczyński, 106-10. |

| ↑41 | Olson, 187. |

| ↑42 | Juszkiewicz, 66-8. |

| ↑43 | Paul S. Scarlata, Mannlicher Military Rifles (Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray Publishers, 2004), 51-64. |

| ↑44 | Scarlata, 74-86. |

| ↑45 | Deszczyński, “Polski eksport sprzętu wojskowego w okresie międzywojennym (Zarys problematyki),” 105–7. |

| ↑46 | Olson, 40-2. |

| ↑47 | Howson. 103. |

| ↑48 | Mario Ojeda Revah, Mexico and the Spanish Civil War (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2015), 114. |

| ↑49 | Revah, 110. |

| ↑50 | Orwell, 35-6. |

| ↑51 | James B. Hughes, Mexican Military Arms: The Cartridge Period, 1866-1967 (Houston, TX: Deep River Armory, 1968), 120. |

| ↑52 | Howson, 103. |

| ↑53 | Cecil D.Eby, Comrades and Commissars: The Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007), 47. |

| ↑54 | Xosé Manuel Suárez, “La Tragedia Del Mar Cantábrico y Otros Apresamientos Navales En La Guerra Civil” (Drassana no. 18, 2010), 76. |

| ↑55 | Howson, 276. |

| ↑56 | Paul S. Scarlata, “La Guerra Del Chaco: The Bloodiest Latin American War of the 20th Century: Part I.” Shotgun News, April 20, 2014. |

| ↑57 | Bernardo Neri Farina, José Bozzano y La Guerra Del Material (Asunción, Paraguay: El Lector, 2011). |

| ↑58 | Scarlata, “La Guerra Del Chaco: The Bloodiest Latin American War of the 20th Century: Part I.” |

| ↑59 | Ball, 59-60. |

| ↑60 | Toe Nõmm, “Eesti Sõjapüssid 1918–1940” (Laidoneri Muuseumi Aastaraamat, 2005), 46. |

| ↑61 | Nõmm, 46. |

| ↑62 | Howson, 144. |

| ↑64 | Ball, 116. |

| ↑65 | Howson, 298-300. |

| ↑66 | Howson, 86. |

| ↑67, ↑68 | Howson, 87. |

| ↑69 | Ball, 22-9. |

| ↑70 | Armas Automáticas y Fusiles de Repetición (Burgos: Jefatura De Movilización Instrucción Y Recuperación, 1938), 85-107. |

| ↑71 | José María Manrique García, and Lucas Molina Franco. Arms of the Spanish Republic: A Nationalist Overview, 1938 (AFV Collection, no. 3. Valladolid, Spain: AF Ediciones, 2007), 69. |

| ↑72, ↑73, ↑74, ↑75 | Manrique García and Franco, 69. |

| ↑76 | Patrick Brogan and Albert Zarca, Deadly Business: Sam Cummings, Interarms, and the Arms Trade (New York: Norton, 1983), 126-27. |

| ↑77 | Golden State Arms. Corp, Advertisement. Guns Magazine , May 1957, 2. |

| ↑78 | Ma Hunter, Advertisement, Guns Magazine, June 1957, 56. |

| ↑79 | Potomac Arms Corp., Advertisement. Guns Magazine, October 1960, 41. |

| ↑80 | Brogan and Zarca, 126. |

| ↑81 | Brogan and Zarca, 106. |

Awesome content dude — thanks so much for posting! Will the rifles of the Nationalist forces come next?

Thanks! I’ve considered exploring that topic as a follow-up. I’m currently researching Japanese rifles for an article planned for the near future.